About

The Battle of Camden

STAGING

Charleston fell to the British on May 12, 1780, with the surrender of more than 5,000 Continentals, state troops, and militia. In June 1780, the hero of Saratoga, Major General Horatio Gates arrived in the South with plans of replicating his victorious campaign in the North. Gates marched for Camden to capture the outpost there. Major General Baron de Kalb and more than 1,000 Maryland and Delaware Continentals left Morristown, New Jersey, on April 16 with orders from General George Washington to reinforce General Benjamin Lincoln in South Carolina. They made it to North Carolina when word of Charleston’s surrender reached them, and they moved to join Gates. Lt. General Charles Earl Cornwallis in Charleston learned of Gates’ march and arrived the night of August 13-14 at Camden. He knew “that the disaffected country…had actually revolted, and that Lord Rawdon was contracting his posts and preparing to assemble his force at Camden.”

While marching toward Camden, Gates’ troops “frequently felt the bad consequences of eating bad provisions.” Colonel Otho Holland Williams wrote of the army’s inability to forage for food and eating green corn “which was attended with painful effects. Green peaches also were substituted for bread and had similar consequences… It occurred to some that hair powder which remained in their bags would thicken soup, and it was actually applied.” The effects of this ill-advised diet would impact the men in the upcoming battle. Just prior to the battle, Gates’ men were “breaking the ranks all night and were certainly much debilitated…”

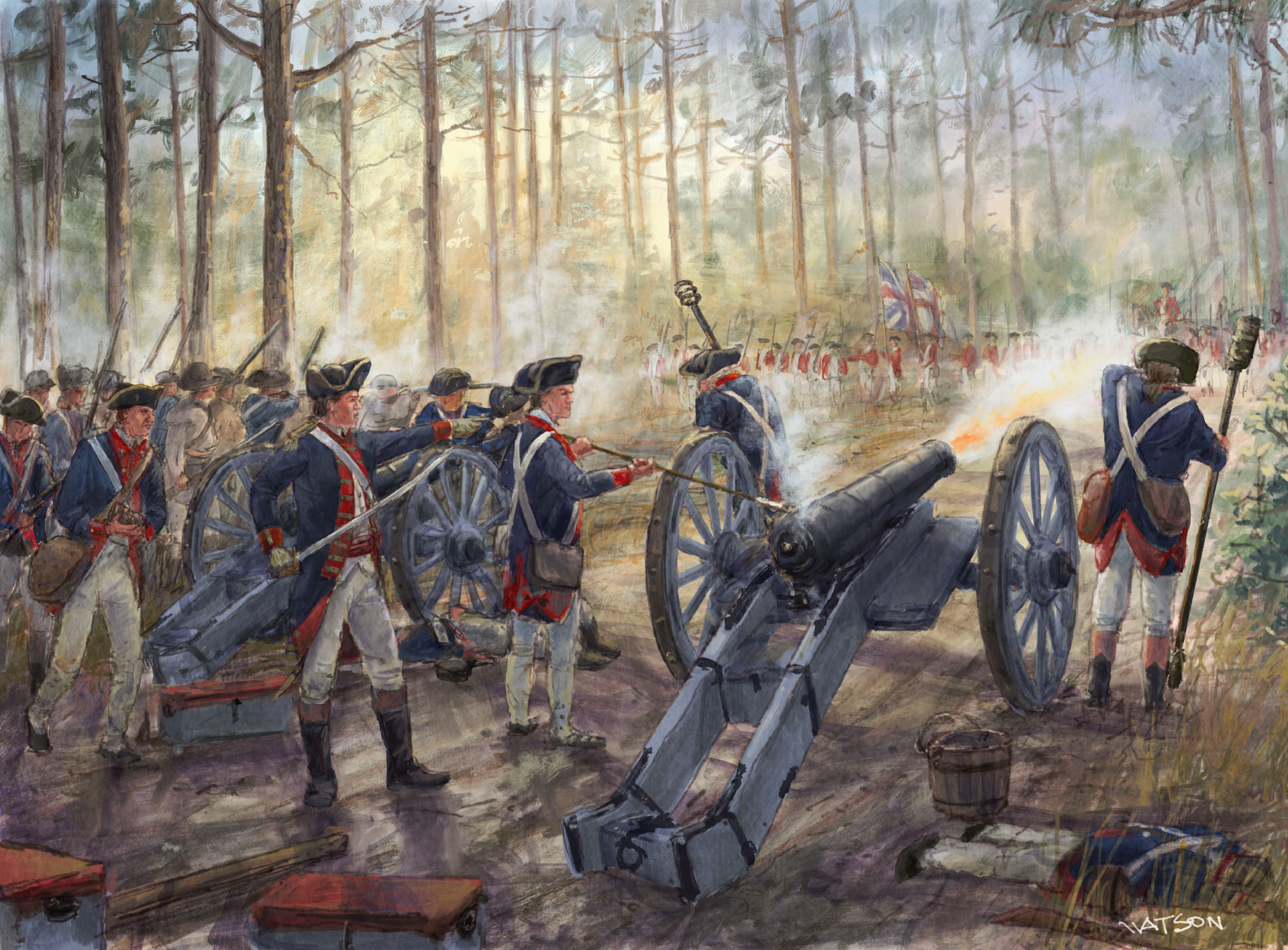

Both armies executed a full moon, night march on August 15. The two opposing armies’ vans literally ran into each other on the Waxhaw’s road eight miles north of Camden on August 16 at about 2:00 AM. Continental Colonels Charles Armand and Charles Porterfield clashed and skirmished in the dark with British Lt. Colonel Banister Tarleton. Both sides fell back to regroup. At early morning light, the two armies faced each other about 200 yards apart on the under-forest of longleaf pine.

BATTLE

The British force of 2,335 troops, commanded by Cornwallis faced off against the American forces who numbered above 3,500, nearly 2,250 of whom were inexperienced new Virginia and North Carolina militia. De Kalb’s 900 Maryland and Delaware Continentals were arrayed on and to the west (right) of the Waxhaw’s road. To the east (left) of the road were placed 1,800 North Carolina militia and to their left was 700 Virginia militia. Armand’s calvary and the Maryland 2nd were held in reserve. Lord Rawdon commanded his own Volunteers of Ireland and the Legion calvary on the British left wing. Lt. Col. James Webster commanded the most seasoned 23rd and 33rd Regiments on the British right wing. Ironically both Gates and Cornwallis place their most experienced troops to the right opposing the enemy’s less experienced soldiers.

ILLUSTRATION: DALE WATSON

ILLUSTRATION: DALE WATSON

The British right flank opened the battle by attacking the American left at the heart of the militia. Patriot Brigadier General Edward Stevens ordered his men to fix bayonets, which in combat they had never done before. In the face of an aggressive bayonet charge from the British, many Virginians and then the North Carolina militia fled before the British regulars reached them. Many men dropped their muskets and fled without having fired a shot.

The right wing under de Kalb was attacking after receiving the order from Gates. They had no idea how bad things were on the left because the dawn’s dead calm had left the smoke from artillery and gunfire lingering in a haze under the trees. The Maryland and Delaware regulars twice repulsed Lord Rawdon’s Volunteers of Ireland and then inserted successful counterattacks. Cornwallis rode up and directly rallied his men. Meanwhile, Webster controlled his British right to wheel left and continue as an oblique flanking assault into the Continentals, instead of pursuing the fleeing militia. A remaining North Carolina regiment closest to the Delaware Continentals was the first hit by Webster’s flank attack. Marylanders fought off Webster’s attack, but less than 800 Continentals were facing at least 2,000 British regulars. The final blow came when Cornwallis ordered Tarleton’s British Legion slashing through them and back again from the American rear. Under this cavalry melee, ranks finally broke. Some Americans managed to escape through nearby low pocosins. De Kalb suffered eleven wounds before falling.

AFTERMATH

The longleaf pine forest battlefield was taken by the British after one hour. Despite numerical superiority, the Patriot forces endured a humiliating rout—one of the worst defeats in American military history. Perhaps 2,000 Americans fled the action without firing at all. As many as 800–900 Patriots were captured or killed. Tarleton pursued the fleeing Americans with a short skirmish action at Granny’s Quarter Creek and then chased them north above Hanging Rock for more than 20 miles before finally turning back. The British sustained about 350 casualties. Tarleton would overcome General Thomas Sumter at Fishing Creek on August 18.

Gates suffered horrendous humiliation for this defeat and his three-day “panic” horse-ride of 180 miles to Hillsborough, North Carolina. Gates wrote, “I endeavored …to rally the militia at some distance…but the enemy’s cavalry continuing to harass their rear, they ran like a torrent, and bore all before them.” His battle actions were questioned. Gates demanded a court martial inquiry and he was furloughed home to western Virginia. Major General Nathanael Greene replaced Gates as commander of the Southern Department in December 1780. Never again would Gates hold field command, though he served on Washington’s staff at the end of the war. Wounded and captured, De Kalb died three days attended by Cornwallis’ physician.

This one-sided British victory strengthened Cornwallis’ resolve to crush the Patriot rebellion in the South. Cornwallis asserted, “The Rebel Forces being at present dispersed, the internal commotion and insurrections in the Province will now subside.” This would prove more costly and elusive for the British than he ever contemplated.