Creating the Declaration of Independence

Written by Rick Wise, CEO & Military Historian

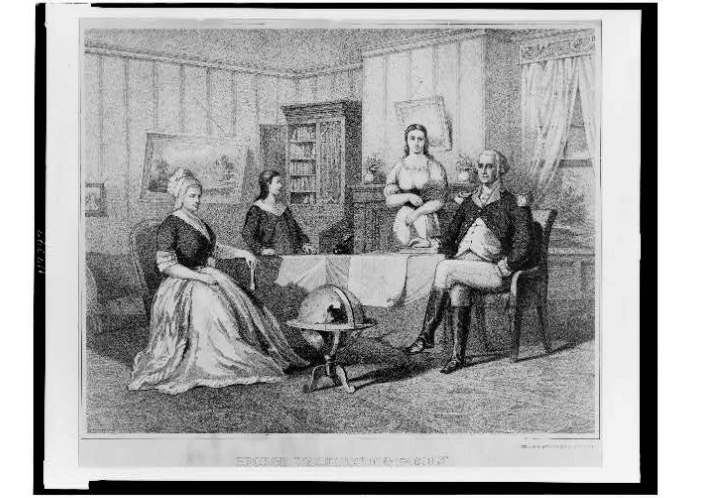

Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams meet at Jefferson's lodgings, on the corner of Seventh and High (Market) streets in Philadelphia, to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee formalized a resolution stating in part, “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown…” A vote on the resolution was delayed until July 1 so that delegates could get guidance from their home legislatures, and it also gave time for those still seeking reconciliation to convince others of their views. Meanwhile, a committee of five was established to draft the declaration, so that it would be available should the resolution for independence pass. Moderates were greatly concerned, since passing such a resolution would mean no further possibility of returning to the way things had been before.

Now, after 249 years, we know it all worked out and the fledgling nation is now the most powerful in the world. But the reality of the time was far from predictable. Each representative in the Second Continental Congress understood that their own hides were on the line. What they were doing, especially since they would now be officially critical of the king, could be called treason, payable with your property, your fortune, and your life. Should the effort for an independent America fail militarily, there would be a price to pay for these delegates, and there was no certainty of the outcome.

After Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was passed on June 7, three committees were established. The Committee of Five to draft a Declaration of Independence was appointed on June 11, and included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. A committee was also formed to establish the War and Ordnance Board, and another to draft the Articles of Confederation to unite all the states. That’s right, to be called the United States of America.

When the Committee of Five for the Declaration of Independence met, Franklin suffering from gout, declined to be active. He also clearly stated that he had no desire to draft a document that would be edited by a committee. Adams was focused on the Board of War and Ordnance, of which he would chair and then become the de facto Secretary of War. The other declaration committee members focused on the more important work going on for those other committees. That is correct, more important work. Drafting the Declaration was considered by those on the committee to be a minor administrative chore. And there was a man to do it. Six foot- two Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, a 33-year-old lawyer. He was a gifted writer, but was notably a very poor public speaker, a man who rarely spoke out in congressional sessions.

Once the committee agreed on a framework for the constitution, it was turned over to Jefferson. Adams, who was not well liked by many in Congress, believed that a draft attributed to himself would be too severely scrutinized. The committee left it to Jefferson to draft the declaration, which was considered less impact than the committee members’ other tasks. Little did they know how history would view it today.

Jefferson initially focused on writing a draft constitution for Virginia, not the Declaration. But in doing so, he drew from it points to be made of the wrongs inflicted on the colonies that were included in the draft Declaration. He thought that using “Whereas,” found in legal documents, gave the Declaration too much of a royal sounding beginning. Instead, he opted for another opening, “When in the course of human events….” The draft was completed on the third week of June and presented to Adams and Franklin. Amazingly, these most learned of men recommended only one change. Instead of “sacred and undeniable,” they suggested using a now often recited phrase, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…”

The draft declaration was presented to Congress on June 28…the same day those in Charleston were focused on more immediate events taking place in the harbor at Fort Sullivan, that resulted in a decisive victory for America. A victory that would have likely given resolve to the representatives had they known what had occurred in South Carolina.

Debate of the Resolution for Independence took place in Congress on July 1 and 2. John Dickenson of Pennsylvania was still adamant that diplomacy had not run its course. Those in Charleston, after the events at Fort Sullivan, were pretty sure that diplomacy had run its course, and that the issue would now be decided by force of arms. On the second vote, on July 2, the delegations voted 12-0 to pass the resolution. New York abstained as they did not yet have guidance from home, but did add their affirmative vote on July 9.

John Adams predicted that, “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable … in the History of America … It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” American is still celebrating 249 years later, proving him right! But he did get the date wrong. He did not know that 85 edits later, the Declaration would not get to the printers until Thursday, July 4, 1776, the date that was put on the document. It was then sent, without signatures, across the now 13 states, so declared on the document as being the Unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America. It was ordered to be read to the troops and the people. The signatures were added to it on August 2…and it was said there was total quiet in the hall. Each signature bore the possibility of grave consequences for each of the 56 men whose names appeared there. It was a somber experience, As Benjamin Franklin said about those fomenting change for the country, “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, then we shall all hang separately.” Such was the gravity and uncertainty of those times.

The unsigned Declaration arrived in Charleston August 2. On that same day in Philadelphia, the majority of representatives finally signed the Declaration. Those representing South Carolina were Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton, and 26-year-old Edward Rutledge.

On August 5, 1776, the local militia formed at noon time on Broad Street, and, with President Rutledge, General Lee, their staff members, legislators, dignitaries, and citizens listening, the Declaration was read. The whole assembly then moved east down Broad Street to the Exchange Building, where it was read a second time, and which event we honor by our presence here this morning. The crowd cheered, and cannon salutes thundered along the Cooper River. The Declaration was then read to the assembled Patriot troops that night by Major Bernard Elliott near the Liberty Tree north of Charleston. The next day it was read to the troops at Fort Moultrie and Fort Johnson.

But the war was not over. The Declaration of Independence, with its desire for a nation derived from the consent of the people, became reality due to the sacrifices of the anonymous many who paid the ultimate price, here, and on battlefields across America, not for liberty they would get to experience, but for the liberty of others. We owe them our sincere and most humble thanks, for without them, we would not enjoy the benefits this great nation bestows upon its citizens for the past 249 years. Thank God for the inspiration of our forefathers, for our State, and our Nation. Huzzah, and God Bless the America!